“Dancing a Path to True Love, A Flamenco Romance Memoir,” by Marianna Mejia

These excerpts are from “Dancing a Path to True Love, A Flamenco Romance Memoir”

©2023 Marianna Mejia

Bea

On her own while her husband was off with the Merchant Marines, Bea had no childcare and needed to work. Listening to the advice of a social worker, she put Freddie with a foster family and Dorothy, who was already seven-and-a-half, in the Mount St. Joseph orphanage. Bea would visit with the children on weekends, often bringing them home for those days. On one of those visiting days at home, Freddie and Dorothy decided to clean a piano on the premises. Copying the adults they saw cleaning floors, dishes, clothes and more, and wanting to do a good job, they used plenty of soap and water. In their innocence and helpfulness, they had no idea that they were badly damaging the piano. And that is when Bea came to them with the news, telling them simply, “Your father has drowned. He will not come home.” Freddie told me later, that at six, he had been too young to know what dead was. He remembers jumping up and down on a couch after that. But his little boy prophesy had been proven true. The story around his father’s death was muddy. The official story was that while the boat was docked in Manila Bay, the crew had been playing volleyball and the ball had fallen into the water. They said that Freddie’s father had jumped overboard to get it. “He was a poor swimmer,” the Merchant Marines told them.

“But that’s not true,” Freddie’s mother countered. “He was a wonderful swimmer. I’ve often seen him swim.” And Freddie’s father, being from the Philippines, would never have jumped into the shark filled bay. His family wondered if there had been an unpaid gambling debt and if other sailors had pushed him overboard. Instead of actually drowning, Freddie’s father had probably been attacked and eaten by the sharks. Freddie was convinced of that by the time he first told me the story.

At the foster home, six-year old Freddie was made to sleep in a crib and the other kids used to tease him and grab his hair to knock his head onto the wall of a closet. The foster father had pus-filled boils over his body and used to make Freddie squeeze them. A short time later, little Freddie was sexually abused by both the boys and the girls there, and fortunately he told his mother. Bea, incensed, stormed over to the house and pounded on the door. When there was no answer, she threw a rock through the window, reached in to unlock the door, and ran inside. There she found Freddie, wet in his crib, holding a live wire that the foster parents used as an antenna for their radio. Bea carried Freddie out immediately and brought him home. Then she retrieved Dorothy. “Enough of this!” she decided, “My children belong with me.”

For a short time, the family actually lived with the social worker, a kind woman named Mrs. Slocum. With the help of the social worker, Bea found a home in some newly built housing projects, the Sunnydale projects in South San Francisco, near the Cow Palace. When they moved there, shortly after World War II had ended, the project housing was brand new and clean, and was bordered by green hills. Rumors said that it was built on a Native American burial ground and it had a sacred quality about the land. The grass had yet to grow next to the sidewalks and Freddie’s mother even found unused earth on the premises to cultivate a small vegetable garden. She planted peppermint and honeysuckle outside and grew sprouts in the dark closet under the stairs. When the door was opened, the smell of sunless earth would burst out and overwhelm the senses, forcing the kids to quickly slam the door shut again.

The shining, lower-class project was filled with the poor, many of them immigrants –Irish, Italian, and working-class whites. The kids hiked in the wilderness just beyond the buildings, roaming unsupervised in the nature around them, and there was an air of hope and new beginnings. Small family-owned neighborhood grocery stores served the area. Bea had brought her family to a nice home, poor though they might be. Unfortunately, she still couldn’t afford a guitar for her young son.

Their mother had also put Freddie and Dorothy in yoga classes and East Indian dance, yet it was Flamenco that grabbed Freddie’s soul, as it later would mine.

***************************************

When Freddie’s mother, Bea, visited, she found the child in dirty diapers with worms, living in an apartment filled with moldy dishes, rotten food, and filthy clothes strewn over the floor. “I’m taking him,” she announced, “This is no way to care for a child!” And so Manolo lived with his grandmother Bea who had re-married by this time, and his two uncles, who were only several years older than he was. Bea was fiercely protective and adored her first grandchild. Timmie and Terry, his uncles, loved him like a brother and he became an integral part of their family unit. Then one day there was a knock on the door. Betty Jane and her critical mother were standing there.

“We have come for Manolo,” they stated, and grabbed the child and left. Bea was distraught, crying, “My baby. My baby.” When I met Freddie, he used to tell me about his lost son. He had no idea where he was or how to find him.

***************************************

Bea was a character. She had grown up in Texas, in a large, “brown-skinned family with the last name of Wolfe. We never fit,” she said. “Our looks didn’t go with our name.” Her background was primarily German, Mexican Indian, and Spanish. Saddled with the first name of Perfecta, and the teasing that went with it, she later went by her middle name, Beatrice. She was the family scapegoat. Her older sisters used to hide her shoes so she couldn’t go to school or they would take her books. She wanted so much to learn, but her family discouraged her and, without shoes to wear, she dropped out after the third grade. She was made to constantly care for her younger brothers and sisters instead of learning to read and satisfying her intense curiosity. Finally, tired of being continually abused by her many siblings, Bea had run away to California at fifteen, hitchhiking with a friend to Los Angeles. They both took on fake names and identities. Bea’s was Mary Drake.

In Los Angeles, needing money, she got a job being a nanny, which distracted her from continuing on to her original destination, Monterey. At seventeen, still in Los Angeles, she met and married Freddie’s handsome and religious, playboy father, recently emigrated from the Philippines.

Freddie senior, a gambling, literate man with beautiful handwriting, dutifully wrote home to his mother weekly. He played the ukulele and must have had a lot of charisma for Bea to stay with him. She always claimed he was the love of her life. Bea was never religious and couldn’t read when she met him, although he did teach her to read. Later he started to beat her. Scared and frustrated, she hitchhiked with Freddie and Dorothy to see her family in Texas. But some of her sisters’ children called Freddie and Dorothy names, because they were half Filipino, and those cousins burned little Freddie’s ear with cigarettes. When Bea discovered what they had done, she immediately left with her children, without telling her family why or goodbye, and returned to her abusive husband.

Later, when Freddie was five, Bea signed Freddie senior up for the Merchant Marines and it was on one of those trips that he mysteriously ended up in the shark-filled Manila Bay, never to be seen again. Although the merchant marines listed him as drowned, Freddie, as he told me soon after we met, remained sure his father had been eaten by the sharks. Even though the official report stated that Freddie senior couldn’t swim, Bea always said he had been a surfer in the Philippines and was an excellent swimmer. She and her children continued to believe that he had been pushed overboard. But they couldn’t be totally certain. Bea felt guilty for having signed him up for the Merchant Marines, which she had done in a fit of exasperated anger at his gambling. Now she had recurrent dreams of her dead husband telling her something, but she always woke up before she could understand his message. “Hypnotize me,” she later used to beg. “I want to know what he was telling me.” But, unfortunately, I never got around to this.

Perhaps influenced by Freddie’s unfaithful, playboy father, Bea called all Freddie’s girlfriends floozies. According to Bea, none of Freddie’s girlfriends were good enough for him. Because Freddie and I were just friends, Bea and I got along. Like me, she was interested in nature, natural and healthy foods and natural medicines. “I believe in nature,” she told me. “Nature is my religion.” She seemed very unlike what I had heard about her dead husband. When her children were still young, after she had moved to the Bay Area from Los Angeles and had finally learned how to drive, she would drive them into the Berkeley hills, make them go outside the car, and tell them to breathe. She wanted them to feel the clean air and to be a part of nature. Bea was always doing some kind of cleanse, whether with lemon and cayenne, or juice. Alternative health was one of her favorite interests. Although she had only gone to school through the third grade, Bea was inquisitive and original. She had a mind of her own and a stubbornness to go with it. She called it “tenacity.” Bea was certainly unusual for her time period in history.

While living in San Francisco after Freddie’s father had died, Bea met her second husband and had two sons with him, Terry and Timmie. She fought with that husband over his continual gambling and separated from him several times. He had already died by the time she and I were first introduced, and Terry and Timmy had grown up.

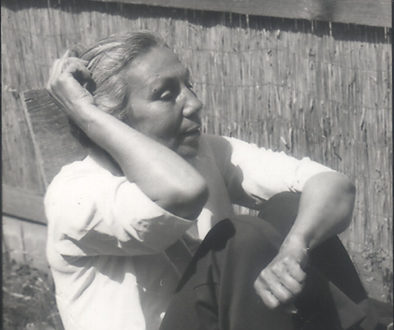

Shortly after we met, Bea moved from Berkeley to Monterey, the city she had always wanted to live in. That made it easy to drive her big, blue Dodge, “The Bluebird of Happiness” to Watsonville to visit us when Freddie was living there. Bea was in her sixties when she finally learned how to drive. After getting her license, she had taken a shop class filled with young boys. There she had painted her new, second-hand car bright blue. She drove with white gloves on her strong hands. Bea loved her children and became disdainful when I called them kids. “They are not goats!” she would tell me emphatically. She also hated that Freddie smoked marijuana, which he did continually. “The devil’s tail,” she called it. And she always wanted to cut Freddie’s hair short, to “cut off old, bad energy.” She would have preferred him to look like his military photo, (Insert) yet she proudly followed him to his Flamenco gigs, in spite of his long, bushy hair and flamboyant colors. Oh how I wished that my mother had such pride and belief in me. But, unlike Freddie’s mother, my mother subtly belittled me, making me feel inadequate, “not good enough.”

Later, Freddie and Jenny moved to Hawaii for a year where several of our friends visited them. Freddie got a job playing Flamenco at the Hyatt Regency and became good friends with a Hawaiian slat key guitarist who also played there, Hank Kaahea. Many of our friends made the trek to see them in that island paradise. Even Bea visited them, flying in an airplane for the first time. She was overwhelmed by the extreme beauty of Hawaii, calling it a spiritual experience.

After Freddie and I got together, he would have me walk outside with him in the evenings. “Breathe,” he would tell me, “Breathe. Feel the air in your lungs.” That is when he told me the story of Bea taking her children into the Berkeley hills to breathe the air, to be one with nature.

***************************************

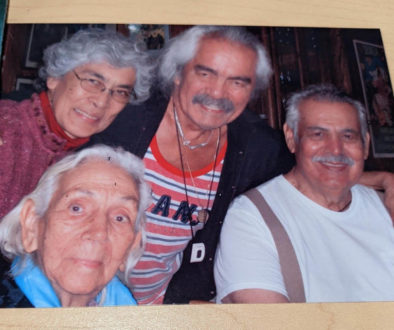

At that Dickens Faire, Freddie had a booth selling chai, and his tall, grey-haired, brown skinned mother was working in it. She wore a period style white cap and apron, and I was impressed that she was so involved with his alternative life.

©2023 Marianna Mejia